Slips and capture and the killing of Daunte Wright

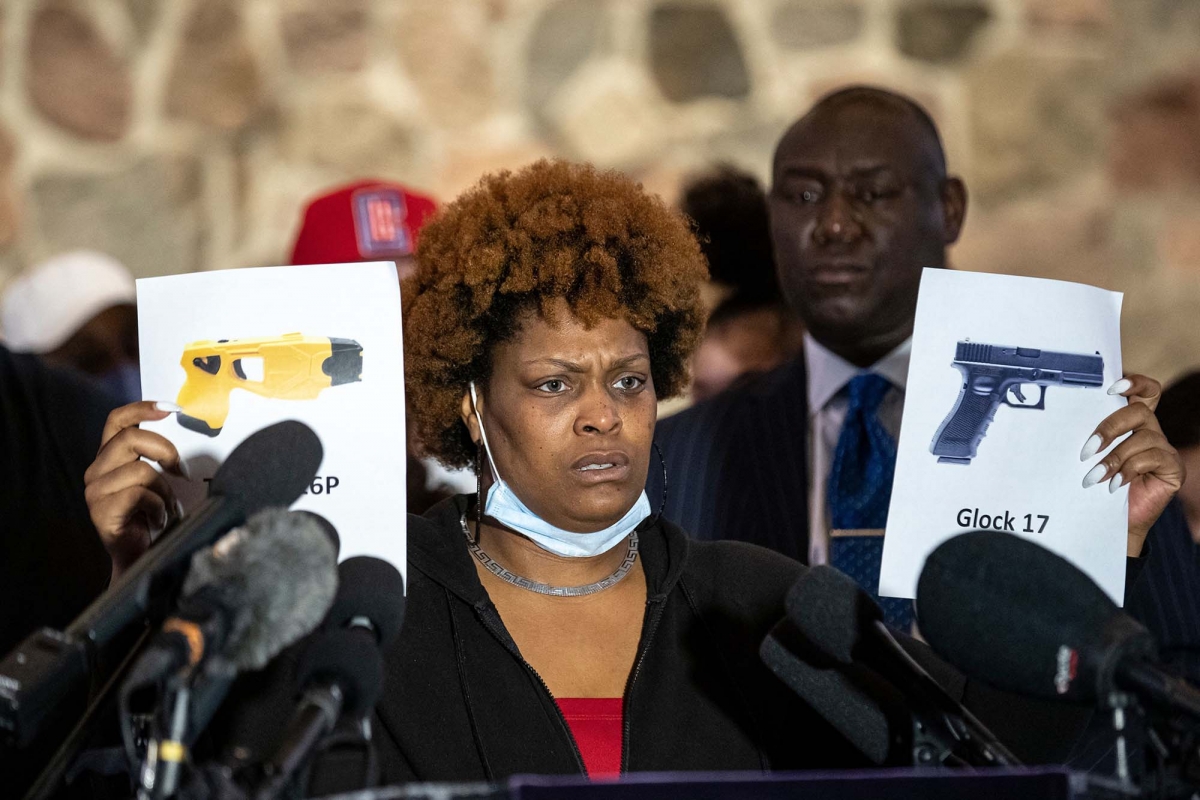

The killing of Daunte Wright rises an important question: how is it possible that a police officer can mistake a black service gun, holstered on the right hip, for a yellow Taser, holstered on the left hip?

The question is legitimate, and to a profane the statement provided by officer Kim Potter, that she mistook her service gun for the Taser she meant to use instead, must sound utterly preposterous.

Only, it isn’t.

The “slips and capture” is a psychological mechanism well known by professionals dealing with safety procedures and error prevention: a person meaning to do something may instead end up doing something else entirely.

It may even have happened to you when, still sleepy from and early rise, you meant to make tea but you instead made coffee, because you always do coffee in the morning, or while driving to go some new place near a path you daily make while preoccupied with something, you ended up the place you usually go instead of the one you meant to go.

It’s far more frequent under highly stressfull and agitated situations, in which it may have far more grievous consequences than just being annoying or embarassing. It’s something that has happened with emergency equipment, with medications in ER rooms, and with firearms as well, and those who train or undergo training in the use of firearms should be aware of it.

But how is it possible to mistake a firearm for a Taser?

Basically, it has to do with training and with conscious, deliberate action vs. unconscious, ingrained “automatic” action.

The subject starts out meaning to do something (i.e.: getting the taser) and begins to do it, then under stressful and agitated circumstances his conscious mind gets diverted by something that requires immediate attention (like a suspect fighting fellow officers and making the person fear for his life) and his conscious mind “slips”: it’s now that his subconscious mind “captures” the slipping action, and carries it on automatically.

Glock 17

Taser X2

Only, this automatism is performed through the most ingrained paths in the motor centers, like for example by having practiced thousands of times drawing your handgun from its holster, compared with few repetitions of getting the taser from its holster on the left hip.

Since the attention of the subject is completely focused on the perceived threat (tunnel vision) he may not even see the gun in his own hand, and his brain will not actually perceive the difference in color from what he was supposed to draw: he’s going on autopilot now, performing the most ingrained action, and what his eyes see his brain either doesn’t register, or finds consistent with said ingrained path.

As of today, there have been 16 cases of an officer mistaking the service gun for a Taser, 4 of which fatal.

How can such cases be prevented?

Specific training addressing the problem is the answer. Training predominantly with the service handgun while dedicating very little training to Taser use will ingrain preferred paths and will make slips and capture mistakes more likely. Training in a comparatively stress-free environment as the square range also does nothing to help officers deal with the extreme stress of a real life-and-death situation.

While in certain situations departments have started issuing lethal and LTL weapons to different personnel, so that an LTL operator can’t possibly mistake the LTL option for the lethal one, this is not always possible.

“Train as you fight” is always sound advice.