Uberti Winchester 1866 "Yellowboy": 150 years for a legendary rifle

The Uberti 1866 replica celebrates the 150th anniversary of the legendary Winchester 1866 “Yellowboy” rifle, the Gun that Won the West. Let's go through the main events that brought to its development.

The original Winchester 1866 rifle (left) used to realize the Uberti 150th anniversary engraved replica (right)

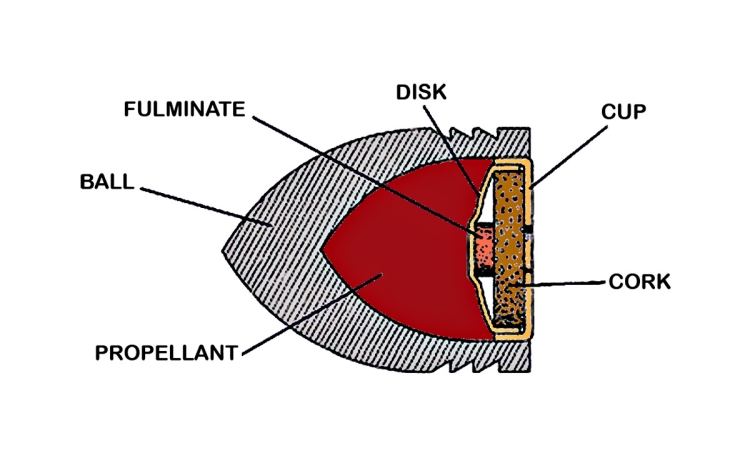

We use to say that the world has grown smaller with time, and perhaps it is true. But thinking about the small circle of XIX century American gun designers, it was even smaller in 1866 or, to be more accurate, and start our story from the beginning, in 1855, when a certain Horace Smith partnered with some Daniel B. Wesson to form Volcanic Repeating Arms Company, a firm intended to develop a promising design: the “Rocket Ball”, an ammunition patented by Walter Hunt, the prolific New York inventor whose brainchilds include the modern (lockstitch) sewing machine and the safety pin.

As the safety pin, the Rocket Ball was a simple yet effective idea meant to circumvent the drawbacks of the then widespread paper cartridge (mainly fragility and sensitivity to water) which would have a great, if indirect, impact on firearm design.

A Minié ball with an enlarged cavity was filled with powder and sealed with a priming cap. Compared to the frail paper catridges, these compact bullets were so solid that they could be put into a tubular magazine of a repeating gun, and fed one after the other by operating a lever.

This was the Volcanic Repeater, working on the first effective repeating mechanism different from the revolving principle to see widespread use (and the first mechanically repeating, breech loading caseless firearm).

The innovative "Rocket Ball" ammunition desigend by Walther Hunt in 1856, to be used in the Volcanic rifles and pistols

The principle was interesting, so the company acquired new investors, among them a businessman active in the textile industry, with factories in New York and New Haven: Oliver Winchester.

Unfortunately, the Rocket Ball suffered from a fatal drawback: the principle was sound, but the cavity could hold only a small quantity of powder.

So small, indeed, that the ballistic performance was in the 70-80 joule range… even less of a modern .22 or .25 caliber cartdidge.

A beautiful original Volcanic repeater, the rifle developed for the Rocket Ball caseless ammunition designed by Walther Hunt

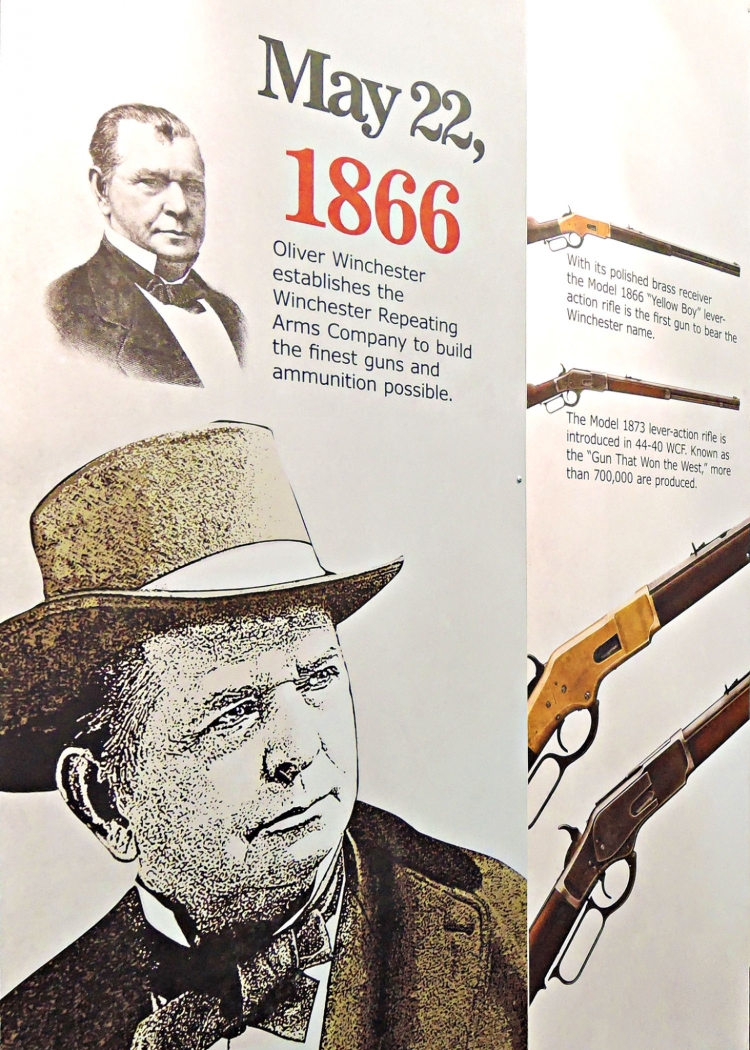

May 22, 1866: birth of the Winchester Repeating Arms Company

This put an end to the Volcanic Repeater and Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson moved on to form their own company: Smith & Wesson. But Oliver Winchester was not to be put off so easily: the cartridge could be lacking in power, but the repeating action of the Volcanic rifle was something unprecedented and extremely promising.

Winchester moved the company to New Haven renaming it New Haven Arms Company and, with the help of Benjamin Tyler Henry, a talented gunsmith from New Hampshire, modified the Volcanic rifle and designed a new metallic cartridge: the .44 Henry rimfire (in homage to Henry's genius, still today, all Winchester rimfire ammunition have the base of he case stamped with a capital H).

Patented in 1860, the Henry rifle was an instant hit, becoming popular among unionist scouts and skirmishing units in the American Civil War, gaining the definition of “the Yankee rifle you load on Sunday and shoot all week long”, assigned by the astonished confederate troops armed with muzzle loading muskets.

The Henry had a rifled barrel and tubular magazine machined out of a single solid steel bar. The magazine loaded from the front, by compressing the spring towards the muzzle, until the spring tube could be rotated and the mouth of the magazine freed. The cartridges were loaded, the spring tube lock rotated back in position and the spring released.

A clear derivation of the Volcanic repeater, but far more effective, the Henry Rifle represents a revolution in firearms history (here a Uberti replica)

Both barrel and magazine of the Henry rifle were fitted to a receiver which has alternatively been described as being made of bronze or brass. In reality, both descriptions are true, as bronze is usually an alloy of copper and tin, while brass is an alloy of copper and zinc, while the Henry receiver was made of an alloy called “gunmetal” composed of copper, tin and zinc, which had remarkable mechanical properties: easy to cast and machine, sturdy, tough, so resistant to oxidation that it is used to make valves and hydraulic components to this day.

When lowering the lever, the bolt retract, the extractor bring the spent case out ot the chamber, whilst the cartridge carrier - holding a new cartridge - moves up ejecting the spent case.

Pulling the lever back in position pushes the bolt forward, chambering a new cartridge. The rifle is ready to shoot again

The Henry rifle action passed substantially unmodified to the model 1866, that you see in action in the two pictures here. The heart of the Winchester action is a toggle-link bolt, operating like a knee joint. This feeding system was designed to work properly even with the gun held upside down.

By lowering the lever, the knee is flexed, the bolt retreats and the spent case is pulled out from the chamber, into the ejection port. Lowering the lever still further, the cartridge carrier block moves up, alligning a fresh cartridge to the breech while ejecting the spent one (the rifle doesn’t have an ejector).

By rising the lever again, the fresh cartridge was chambered while the carrier was lowered to accept a new cartridge pushed back by the magazine’s spring. Returning the lever to its resting position made the knee joint straight again so that the bolt was solidly locked in place, and the rifle was ready to repeat the cycle.

In 1866, the Yellowboy hit the mind of everyone worldwide, as one of the most sought after innovations ever. From top, three basic Winchester 1866 Yellowboy models from the Italian manufacturer Uberti:

19" Carbine, 24" 1/4 Rifle, 20" Short Rifle, available in several popular calibers

The Henry action was very smooth and fluid and the sturideness of the rifle was far more than necessary for the weak .44 Henry cartridge. Nonetheless, the Henry rifle had some drawbacks.

It had no safety whatsoever: with a chambered cartridge you either had the hammer resting on the firing pin, which was in turn resting on the rimfire primer, or you had the hammer cocked and ready to fire.

An Uberti replica of the Winchester 1866 carbine with 19" round barrel

Finally, the reloading process was complex (impossible on horseback) and the magazine unreliable, with the long open slot of the spring follower allowing any kind of debris to enter the magazine itself, blocking the rifle.

After the end of the Civil War, Oliver Winchester had a quite clear idea about how to fix everything into an improved model, which finally arrived in 1866.

A loading gate was added to the right side of the receiver, allowing to reload even when on horseback. The magazine was sealed against debris, and a wooden forearm was added, to protect the magazine tube and the shooter’s hand against a heated barrel.

The cartridge also was modified, going from a copper to a brass case, which allowed it to bear higher pressures. Curiously, again a half cock notch safety on the hammer was not deemed necessary.

Oliver Winchester renamed the company Winchester Repeating Arms and the Winchester 1866 soon received his famous nickname “Yellow Boy” after the color of the receiver.

These are the main facts that brought to the realization of the Winchester 1866, marking the birth of one of the most influential firearms (and company) in history.

Right view of the new Uberti Winchester 1866 Yellowboy. Along with the revised magazine, the loading gate was the main point of strenght of this innovative project

Like in 1866, the Uberti replica is manufactured through a series of machining processes that obtain the finshed receiver starting from a 5 kg, single block of forged brass

Looking at the left side of the receiver shows the clear connection between this "early" 1866 specimen worked out by Uberti and the typical profile of the receiver of the Henry rifle

This is the plain, standard version of the new 1866 Yellowboy introduced by Uberti. it may seem a standard carbine, but it is not.

The barrel is 20" instead of 19", but more important, the receiver has been redesigned after an original "early" model that Uberti has been able to find. So, this 1866 Yellowboy is a mid version connecting the Henry rifle, with its typical receiver profile, with the later 2nd or 3rd generation 1866 models that we have been used to know thanks to Uberti. And it is realy pleasant to shoot.

Muzzle view of the front sight

The folding leaf rear sight, lowered

The folding leaf rear sight, rised

The basic markings, on top of the barrel

This is the 1866 Yellowboy Flatside 150th Anniversary Edition Rifle, engraved version that Uberti has realized this year to celebrate the 150th anniversary

The arrival of the Winchester 1866 was a total blast, remaining in production till 1898, despite the models ‘73 and the ‘94 had already been marketed.

Selling of the model 1866 were huge: the Ottoman Empire alone bought around 45,000 1866 models, using them in the Russian-Turkish war with such effectiveness that the Russians quickly abandoned their single shot Berdans to adopt a rifle that would become a legend on its own: the Mosin Nagant. It was a small world indeed.

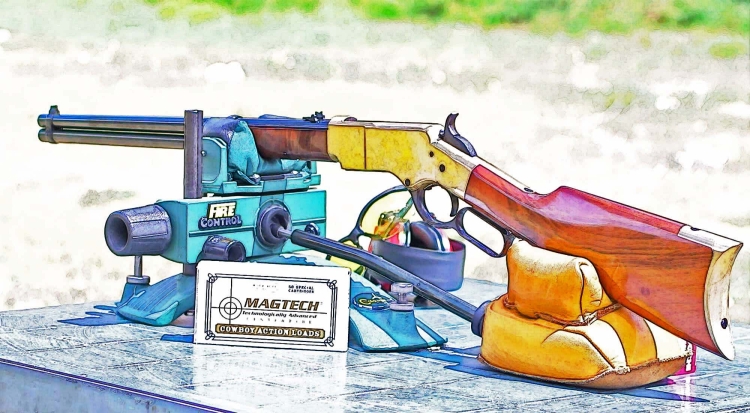

The Winchester 1866 rifle is still a very interesting weapon today, popular with Cowboy Action shooters, western movies enthusiasts, and anyone who wants to own one of the most iconic rifles in the history of firearms.

Luckily, you don’t need to buy a vintage piece (they fetch mind boggling prices on the market, even if not as high as the Henry), as Uberti Replicas are absolutely beautiful and available in several variants.

1866 "Yellow Boy"

The .44 Henry “Flat” rimfire ammunition is no longer available, it has become obsolete, more or less 100 years ago. But the Uberti 1866 Yellowboy is still fuly operative, chambered in several popular calibers, from .22 Long Rifle to .38 Special, .44 Special, .44 WCF (.44/40) and .45 Colt, with 19”, 20" and 24" 1/4 barrels depending on the model and finishes, that can see the bright yellow receiver coupled with charcoal blue, antiqued finishes or premium woods hand rubbed with oil.

The most classical of all lever actions, it’s hard to compare: the yellow boy is just the yellow boy. I should give an aseptic and objective evaluation here, but once you get your mitts on this gun it becomes impossible: you can’t just shrug off its 150 years of history and a hundred western movies come vividly to life in your inner silver screen. I feel it has to be said, for it is integral part of this rifle’s timeless charm.

Finishes are just great: not only every flat surface is finished without the slightest uncertainty, and the deep blueing contrasts pleasantly with the receiver, but markings are deep and in the same, elegant font of the original ones, integral part of the rifle’s aesthetics. The woods show a pleasant figure and the tone goes hand in hand with the receiver’s golden color.

Mechanically speaking, well, it’s a Winchester ‘66: butter smooth action, lightning fast. The round profiled barrel is lighter than octagonal ones and the rifle is very well balanced, the eye finds the sights instantly and the gun is a natural pointer. You can say all you want about straight stocks and straight-back recoil impulse, but whomever designed the Winchester 66 stock knew exactly what he was doing, in terms of fast handling and pointability. And… yes, unlike the originals, the modern Uberti replicas do have a half cock safety notch on the hammer! So, yes, history repeats itself. Improving.