The Spencer carbine

The Spencer Carbine: used during the American Civil War, it was the world's first repeating, metallic-cartridge military rifle.

I don't think there's a single firearms historian who, at the mention of the name Spencer, doesn't respond with a slight sigh, a hint of a smile, and an expression that's a mixture of satisfaction, dream, and longing. In short, the face of someone who not only knows the stuff, but above all wishes they could hold it in their hands, even if only for a moment, to experience the pleasant illusion of being part of the historical period they themselves witnessed.

From this perspective, rather than being witnesses to it, Spencer rifles were protagonists of what has been probably the most important moment in the evolutionary, industrial, and military history of firearms. As General James H. Wilson himself noted during the American Civil War: "There is no doubt that the Spencer rifle is the finest firearm ever placed in the hands of a soldier, both for the ammunition it uses and for the maximum physical and moral effectiveness it is capable of." The Union cavalrymen who began to be issued the first modern Spencer repeating weapons in the late spring of 1862, must have felt invincible when faced with Confederate troops still armed with muzzle-loading weapons.

The Spencer cavalry carbine by Chiappa Firearms, which basically takes on the characteristics of the 1865 model

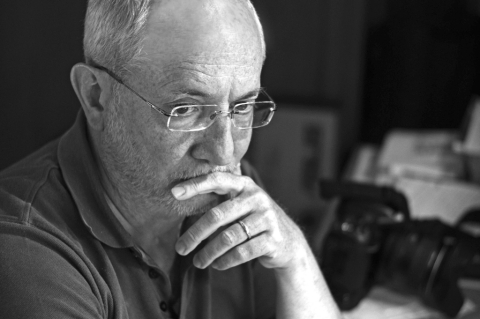

A young Christopher Miner Spencer

The young Christopher Miner Spencer had the initial idea for a repeating, breech-loading long gun as early as 1854, when he was working at the then-technically advanced Colt factories in Hartford.

After refinements and revisions on wooden prototypes, it was only in the spring of 1860 that Spencer was finally able to file the first patent for his new weapon.

That same year, Oliver Winchester was overseeing the patent for the Henry, another major player of the time, while Christian Sharps had recently patented his Model 1859: the innovative fervor in the American firearms industry was at its highest.

Spencer rifles, especially the cavalry versions, were by far the most important repeating weapons—breech-loading and firing metallic cartridges—of the Civil War. Their only real rivals were the highly regarded Sharps rifles: they were also breech-loading, but fired a paper cartridge and were single-shot.

As for the Henry—the progenitor of the Winchester lever-action line—its relative mechanical delicacy and the weakness of its .44 caliber ammunition never allowed it to establish itself in the military field.

In fact, at least for the entire duration of the war, no one managed to break the absolute primacy of the Spencer weapons.

Union cavalry soldiers armed with Spencer carbines

Illustration from the book "The Horse Soldier 1776-1943: the United States Cavalryman - Volume 2, 1851-1880" (Randy Steffen, 1977)

The beginnings, however, were not easy for the young Spencer. In truth, many high-ranking officials in Washington did not appreciate the technological benefits offered by the new repeating weapons. Among them was General Ripley, commander in chief of the Ordnance Board, the body responsible for selecting and procuring Union military supplies: breech-loading weapons, especially repeating ones, were too expensive and posed serious problems in supplying troops with ammunition due to the variety of types used.

At the Navy's invitation, President Lincoln himself contributed to bringing order to the chaos. Through a very shrewd political intervention, he opened the door to the adoption of the new breech-loading weapons, including the Spencer, whose characteristics quickly attracted widespread attention.

Spencer infantry rifles and cavalry carbines were initially chambered for .56-56 caliber rimfire ammunition, the military version of which produced by the Frankford Arsenal used a 450-gram ogival projectile propelled by a 40-gram charge of black powder. Beginning in September 1863, the Union Ordnance Board reduced the number of different ammunition types required for the various breech-loading models then in service, establishing .52 as the standard caliber for all Spencer, Sharps, Joslyn, Ballard, Gibbs, and other models.

12,471 rifles, 94,196 carbines and 58,238,924 rounds of ammunition are the official figures for the military orders placed with Spencer during the years of the conflict between the North and the South, but the overall production of this weapon reached 200,000 units, which in various configurations almost all ended up on the civilian market: so popular during the years of the conquest of the American West that the related .52 caliber rimfire ammunition remained in production on the civilian market until 1920.

Loading sequence of the Spencer carbine

Illustration from the book "The Horse Soldier 1776-1943: the United States Cavalryman - Volume 2, 1851-1880" (Randy Steffen, 1977)

Cavalry soldiers armed with Spencer carbines were issued the Blakeslee Cartridge Box, a bag containing 7 magazines (for a total of 49 rounds).

Description of the Blakeslee Cartridge Box, the Spencer carbine's "Speedloader"

A revolutionary system, in 1860: the removable tubular magazine, holding seven cartridges, inserted inside the stock

The Spencer's feeding and firing system is critical to the design and construction of the individual components, which operate with extremely tight tolerances, but is not at all complicated to understand.

The Spencer's stock is pierced along its entire length by a hole containing the tubular ammunition magazine: inside, a coil spring pushes the cartridges toward the receiver, which houses the weapon's feeding and firing mechanism.

The magazine holds seven rounds and can be easily removed from the buttplate, reloaded, and reinserted, ready for use, with a simple movement.

The tubular magazine of the Spencer carbine

The feeding and locking system of the Spencer carbine, open

Original drawing of the Spencer feed mechanism

Like many other breech-loading weapons of the time, and well before the Winchester lever-action system, the Spencer also uses a lever to control both the opening of the bolt and the feeding mechanism.

The lever also acts as a trigger guard: pulling the lever downward lowers the bolt, exposing the chamber, and subsequently rotating the entire locking block rearward.

At the end of its rearward and downward movement, the locking block is almost completely exposed outside the receiver, beneath it.

In this position, the block exposes the first of the cartridges contained in the tubular magazine, whose spring now pushes it forward—visible to our eyes—into the space left empty inside the receiver by the lowering of the bolt.

1. Unlock the magazine by rotating its tail

2. Remove the magazine from the stock

3. Insert the cartridges directly into the stock

4. Reinsert the magazine into the stock

5. Push the magazine to compress the cartridges

6. Lock the magazine in place by rotating its tail

By applying a firm pull, we pull the feed lever back toward the receiver, thus returning the entire mechanism to its resting position, with the bolt closed.

As it moves upward and forward, the face of the bolt engages the base of the first cartridge in the magazine and pushes it toward the breech of the barrel.

Lever down, bolt open

By lifting the lever, the bolt pushes a new cartridge into the barrel

The magazine spring pushes the cartridges forward, while a fork lever prevents them from exiting the ejection port as the bolt moves. When the bolt closes again, it pushes a new cartridge into the chamber.

The case extraction system is also located at the front of the locking mechanism. It consists of a pair of vertical levers that engage the lateral portions of the case base, extracting it from the cartridge chamber as the entire mechanism moves back.

The upper part of the Spencer's receiver is open, and this is where empty cases are ejected. However, new cartridges, which the bolt draws from the magazine as it advances, would also emerge from the ejection port. To prevent this, a fork lever is hinged to the upper part of the receiver (partially closing the ejection port). A special spring keeps it in constant contact with the locking mechanism.

When the bolt is lowered during opening, the fork lever follows it and acts as a ramp for the upward ejection of the case being pulled from the chamber by the extractor. when the bolt returns to the closed position, taking a new cartridge from the magazine, the hinged fork lever in the upper part of the receiver helps the bolt guide the cartridge towards the barrel, preventing the cartridge from ejecting upwards during the feeding phase.

The gun is loaded, the round is chambered in the barrel: but to fire it is necessary to cock the external hammer.

The lever under the receiver controls only the feeding and bolt mechanism, but not the firing mechanism, which requires manually cocking the external hammer located on the right side of the receiver. The presence of an external hammer was one of the mandatory requirements that the Ordnance Board imposed on weapons undergoing military acceptance testing, and the Spencer, like the Sharps, could not therefore deviate: the movement is identical to that of contemporary muzzle-loading weapons, with a rest position (fully cocked), a safety position (half-cocked), and a firing position (fully cocked).

In a cavity inside the bolt is a floating element, on the right side of which is mounted a plate whose tail is in constant contact with the hammer head: moving in line with the barrel, the block thus transfers the energy received from the hammer's decocking to the firing pin.

First of all, let's say that when using smokeless powder ammunition, it's not necessary to disassemble the gun to clean it after a shooting session. However, for your convenience, let's see how to proceed with a basic disassembly that allows for a more thorough cleaning of the gun occasionally, or if the Spencer is used with reloaded black powder cartridges.

Before proceeding with maintenance on the Spencer, it's always necessary to remove the magazine tube from the stock and verify that the gun is unloaded, meaning there is no chambered cartridge in the chamber.

Then separate the feeding and locking mechanism assembly from the receiver: to do this, simply unscrew the large transverse screw that acts as its rotation fulcrum, visible in the lower corner of the receiver.

If necessary (but it isn't), you can also remove the hammer's spring-rear action plate by loosening its two retaining screws.

Since it's a metal-fired breech-loading rifle, especially when used with smokeless powder ammunition, it's generally sufficient to simply clean the barrel directly from the breech with a thin cleaning rod (preferably fiber).

The need to disassemble the feeding and locking block becomes more significant when using reloaded black powder ammunition, which offers a much greater historical experience but also increases the risk of deposits in the barrel, on the bolt, and inside the receiver.

The sequence for additional disassembly of the bolt components is very intuitive and should only be performed when absolutely necessary (the procedure is illustrated in the manual that comes with every Chiappa Firearms Spencer rifle).

La moderna replica di Chiappa Firearms

In 1992, the presence of a Spencer rifle in Clint Eastwood's movie "Unforgiven" rekindled our interest in this interesting model. However, its relative mechanical complexity did not pique the interest of replica manufacturers, due to the high design and re-engineering costs that its reproduction would entail.

The Spencer continued to remain the preserve of a few owners of vintage originals. Until a few years ago, one of the most well-known Brescia-based companies in the sector, Chiappa Firearms, decided to take on the challenge in response to pressing demand from the US market, undertaking the analysis of the original Spencer design to produce a faithful replica.

The modern replica of the Spencer Model 1865 made by Chiappa Firearms

Two years of work on period originals, including studying the mechanics and completely re-evaluating all the weapon's parts, have finally led Chiappa to create one of the finest reproductions of historical weapons that our specialized gunmaking industry has produced in the last forty years.

The efforts Chiappa Firearms has put into the Spencer project are clearly visible in the mechanical quality and overall finish of their beautiful reproduction of the Spencer cavalry carbine and infantry rifle.

The original .56-56 rimfire caliber Spencer cartridge

The Spencer Chiappa is chambered in .45 Colt or .44-40 Winchester (and .56-50 centerfire, for the US market)

Three aimed shots in .45 Colt caliber, from a rest at a distance of approximately 50 meters

Creating a faithful replica of a historic weapon always involves finding effective compromises between the model's original design and any current technical constraints, such as, in this case, the unavailability of the original ammunition for which the weapon was designed.

Therefore, rather than the original .56-56 rimfire round, Chiappa's Spencer rifle is available in centerfire calibers more readily available to historical enthusiasts and sports enthusiasts, such as the timeless and readily available .45 Colt cartridge or the .44-40 Winchester cartridge, still very popular in the US among Western shooting enthusiasts. Chiappa also makes a .56-50 centerfire version, which, however, is only available in the US, for the many American reenactor enthusiasts.

After the war and the resulting demand for weapons, Spencer was unable to meet the civilian market associated with expansion into frontier territories. In 1869, the Spencer Repeating Rifle Company sold assets and equipment to the Fogerty Rifle Company, which was later acquired by the skilled Oliver Winchester, who was less interested in Spencer than in strengthening the image of the rifle that was meanwhile attracting worldwide attention: the Winchester 1866.

What Winchester couldn't have foreseen was that 130 years later, in Italy, a Brescia-based company would ensure that enthusiasts around the world could once again utter the name of its worst competitor, enjoying firsthand the fruit of an idea conceived in 1854 by a then twenty-one-year-old named Christopher Miner Spencer.